Exploring...

Reading culture in the Victorian underworld

essay author

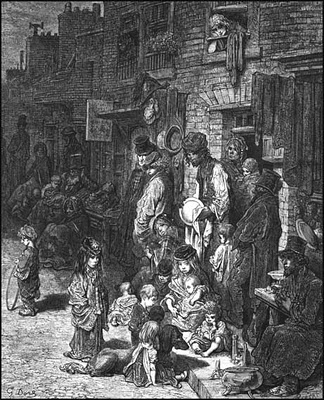

For some years now, we have been treated to many colourful accounts of the Victorian underworld. Documentaries, serialisations of the nineteenth-century classics, neo-Victorian novels and sensational books have evoked the smells and sounds of the slums while exposing the lives of thieves, beggars, scavengers, casual labourers and market sellers. From these accounts, we know a great deal about their dark culture, including the 'flash' language which many used to subvert authority. But where did books fit in to all of this? The nineteenth century was an age of abundant cheap print. Did the slum dwellers take advantage of this? Could these men, women and children even read at all?

This question also intrigued the middle and upper classes of the mid-nineteenth century. Concern about poverty and rising crime rates encouraged a substantial number of men to explore the underworld and they completed detailed studies, often with some statistical basis, on the lives of those who lived below the bread line. Perhaps the most famous of these was Henry Mayhew's 'London Labour and the London Poor', first serialised in the established newspaper, The Morning Chronicle, in 1849-50 and later published as a four volume set in 1861-2. Although rarely acknowledged today, this study helped to unearth a vibrant reading culture among those struggling to survive.

Even Mayhew was surprised to find that such a large number of slum dwellers could read. The two orphan flower girls he found in Drury

Lane 'insisted upon proving to me their proficiency in reading, and having procured a Roman Catholic book, the "Garden of Heaven",

they read very well.'  It is true that this evidence is illustrative of the great

increase in literacy over the course of the Victorian period. But it is worth mentioning that few of those interviewed by Mayhew had

taken advantage of the new charitable educational institutions often championed for eliminating 'ignorance'. Mayhew's interviews revealed

that many costermonger children were taught to read by their parents or siblings. A coster-girl aged 18 explained to Mayhew that her

mother had taught the elder children to read - 'She always liked to hear us read to her whilst she was washing or such like! and then

we big ones had to learn the little ones'.

It is true that this evidence is illustrative of the great

increase in literacy over the course of the Victorian period. But it is worth mentioning that few of those interviewed by Mayhew had

taken advantage of the new charitable educational institutions often championed for eliminating 'ignorance'. Mayhew's interviews revealed

that many costermonger children were taught to read by their parents or siblings. A coster-girl aged 18 explained to Mayhew that her

mother had taught the elder children to read - 'She always liked to hear us read to her whilst she was washing or such like! and then

we big ones had to learn the little ones'.  Some even taught themselves. A 'cheap John'

selling printed songs wished to be able to read them, 'and,' he explained, 'with the assistance of an old soldier, I soon acquired

sufficient knowledge to make out the names of each song, and shortly afterwards I could study a song and learn with words without anyone

helping me.'

Some even taught themselves. A 'cheap John'

selling printed songs wished to be able to read them, 'and,' he explained, 'with the assistance of an old soldier, I soon acquired

sufficient knowledge to make out the names of each song, and shortly afterwards I could study a song and learn with words without anyone

helping me.'  Crucially, while many of these men, women and children could read, they

had not acquired the skill of writing.

Crucially, while many of these men, women and children could read, they

had not acquired the skill of writing.

Literary culture in the Victorian underworld was inclusive: there was no simple dividing line between those who were literate and those

who were not. All found a way to enjoy the range of cheap literature appearing at their fingertips. Sellers of ballads and broadsheets

sung or shouted the contents of their wares to customers. These sheets also contained verses that could be learned by heart and pictures

to gaze upon for those unable to read their short texts. Moreover, families, friends and neighbours often clubbed together to purchase

sheets, periodicals and newspapers - literates and illiterates were not strangers; at least one member of the group would be able to

read to the others. It could be a frustrating experience, as a regular scavenger told Mayhew, 'I likes to hear the paper read well enough,

if I's resting; but old Bill, as often volunteers to read, has to spell the hard words, so that one can't tell what the devil he's reading

about.'  But more often than not, group reading was pleasurable, and of great community

importance. Mayhew discovered a group of costermongers who gathered in the courts and alleys where they lived to hear the 'schollard'

read the latest penny fiction, or 'penny bloods', aloud to them.

But more often than not, group reading was pleasurable, and of great community

importance. Mayhew discovered a group of costermongers who gathered in the courts and alleys where they lived to hear the 'schollard'

read the latest penny fiction, or 'penny bloods', aloud to them.  The costermongers were

not a passive audience: all frequently interrupted the readings, asking for further explanations and giving their opinions. 'Anything about

the police sets them talking at once', explained the 'schollard'. A description of a fierce fight interrupted by policemen with truncheons

provoked this exchange:

The costermongers were

not a passive audience: all frequently interrupted the readings, asking for further explanations and giving their opinions. 'Anything about

the police sets them talking at once', explained the 'schollard'. A description of a fierce fight interrupted by policemen with truncheons

provoked this exchange:

'The blessed crushers is everywhere,' shouted one. 'I wish I'd been there to have had a shy at the eslops,' said another. And then a man

sung out: 'O, don't I like the Bobbys?'

But it would be wrong to assume that the tastes of the poor were confined to cheap trash, full of sensation, violence and crime, and

providing inducements to criminal or otherwise unacceptable behaviour. Perhaps surprisingly, literary culture in the slums included works

that we would regard as high-brow or canonical, works that a reader would need some skill and intellect to decipher and enjoy. Yet the

crossing sweeper who was reading the infamous Reynolds's Miscellany the night before his interview had also read Pilgrim's

Progress three times over!  The crippled penny mousetrap maker, 'for an hour's

light reading', turned to Milton's Paradise Lost and Shakespeare's plays.

The crippled penny mousetrap maker, 'for an hour's

light reading', turned to Milton's Paradise Lost and Shakespeare's plays.  And

a sweet-stuff maker bought unwanted printed paper to wrap his wares from the stationers or at the old bookshops - as he read the text

before he used the paper, 'in this way he had read through two Histories of England'.

And

a sweet-stuff maker bought unwanted printed paper to wrap his wares from the stationers or at the old bookshops - as he read the text

before he used the paper, 'in this way he had read through two Histories of England'.

This represents just a small taste of the sheer variety in reading tastes and practices that Mayhew, and other social explorers, uncovered in the underworld of the Victorian age. Contributors to the Reading Experience Database (RED) have joined these together with other records, from nineteenth century prisons and criminal courts, to provide a truly comprehensive profile of the common reader at a time of cheap print and rising literacy rates. Why don't you try exploring some of these yourself - www.open.ac.uk/Arts/reading/UK/search - I promise you will be amazed at what you find!